Youth Unemployment and the New Economic Geography

Image: Detroit, Michigan, USA.

By Colette Mazzucelli and James Felton Keith

In his recent Foreign Affairs essay, Adam Posen revisits the “new economic geography” (NEG), emphasizing how clustering effects, agglomeration economies, and transportation costs drive industrial location and national competitiveness. While these dynamics remain fundamental to understanding global trade and development, an equally critical—yet underexplored—dimension is youth* unemployment. Though not part of the original NEG models advanced by Paul Krugman and others in the 1990s, youth unemployment reflects, amplifies, and in turn reshapes the spatial economic inequalities those models describe. The integration of AI to support background research in this context is particularly useful in reflecting on a response to Posen's essay.

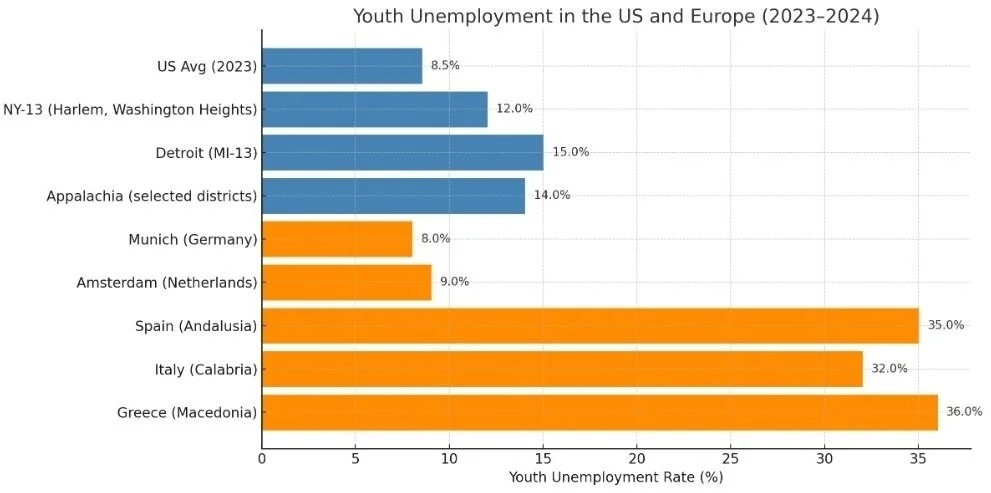

The empirical record, illustrated in the graph, underscores the point regarding youth unemployment. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), global youth unemployment stands at 13.1 percent in 2024, more than three times the adult rate, with regional disparities even starker: nearly 30 percent in North Africa, compared to 8 percent in North America. Within countries, metropolitan regions with dense clusters of firms and universities consistently report lower youth unemployment rates than peripheral or deindustrialized areas. For instance, in the European Union, Eurostat data show youth unemployment below 10 percent in cities such as Munich and Amsterdam, while exceeding 35 percent in regions of Spain, Italy, and Greece. In a comparative perspective, the application of ESRI ArcGIS technology is relevant in terms of geospatial analytics to visualize the data pertaining to youth unemployment across regional settings.

In this context, the United States is no exception. Bureau of Labor Statistics data put national youth unemployment at 8.5 percent in 2023, but regional disparities are striking. In New York’s 13th Congressional District (Harlem, Washington Heights, and Inwood), youth unemployment has consistently outpaced the national average, tied to a combination of industrial decline, housing pressures, and limited pathways to high-wage employment. In Detroit, decades of deindustrialization have left youth unemployment rates hovering around 15 percent—nearly double the U.S. average—even as the city attempts to reposition itself as a hub for mobility innovation. In Appalachian districts, youth unemployment remains persistently high as declining coal production and limited infrastructure investment restrict economic diversification. These localized disparities demonstrate NEG’s central logic: opportunity clusters geographically, often leaving behind regions where industries never arrived or have long since departed.

Beyond descriptive statistics, the implications for economic geography are profound. Persistent youth unemployment undermines the development of skilled labor pools, stifles innovation, and weakens the very agglomeration economies that sustain competitive regions. The OECD has warned that “scarring effects” of long-term youth unemployment reduce lifetime earnings potential by up to 20 percent, entrenching regional inequalities across generations. In the U.S., this means young people in districts like NY-13 or Michigan’s 13th (Detroit) enter adulthood at a structural disadvantage compared to peers in Boston, Austin, or the Bay Area—cities where industry clusters generate abundant entry-level opportunities.

NEG’s formal models may not assign youth unemployment a causal role in determining industrial clustering, but contemporary economic geography must. The spatial distribution of industries and infrastructure directly shapes access to labor markets, training systems, and educational institutions. Conversely, regions with chronically high youth unemployment risk exclusion from new industrial growth trajectories, as firms increasingly locate where human capital is abundant and dynamic. In this sense, youth unemployment is both a symptom of geographic inequality and a mechanism that reinforces this evolving phenomenon.

Policy must follow theory. To date, responses to spatial economic divides have emphasized physical infrastructure—ports, transport corridors, and supply chains. Yet addressing youth unemployment requires equal investment in “social infrastructure”: education systems aligned with regional industry needs, apprenticeship pipelines, targeted job creation programs, and mobility supports that allow young people to access opportunities across regions. Without such measures, the promise of agglomeration will be captured by a few regions while others spiral further into disconnection. This is of particular concern for Europe and North America, which are continents with aging societies, as well as the prospect of dwindling resources to support retirement safety nets looking ahead to 2035.

In short, youth unemployment should not be considered external to the new economic geography. It is central to the lived reality of spatial inequality in the global economy. Where industries go, opportunities follow—but only if institutions and policies ensure the next generation can access them. As the ILO has observed, societies that fail to integrate young workers into productive activity not only lose potential growth but risk long-term instability. The “new geography” of our economies, therefore, is not just about where firms cluster. It is about whether entire generations are left out of those clusters altogether.

*Youth is defined as ages 16-24.

Colette Mazzucelli is Founder and Principal, LEAD IMPACT Reconciliation Institute, Inc. and the first President (Academia) Emerita, Global Listening Centre. Since 2005 she has taught on the Graduate Faculty, GSAS & SPS, at NYU New York, https://as.nyu.edu/faculty/colette-mazzucelli.html. Colette is the Editor of the Anthem Press Ethics of Personal Data Collection Series. A BMW Foundation Responsible Leader, she has served as a member of the Advisory Board of the Syrian Emergency Task Force, https://www.syriantaskforce.org/. At Pioneer Academics, she teaches International Relations (Europe) mentoring students across continents, https://pioneeracademics.com/. Colette is the author and/or editor of seven volumes, including France and Germany at Maastricht, https://www.amazon.com/France-Germany-Maastricht-Negotiations-Contempora.... Since 1993, Colette’s biography appears in numerous Marquis Who’s Who publications, https://wwlifetimeachievement.com/2019/01/07/colette-mazzucelli/.

James Felton Keith is an award-winning engineer and economist who was the first black LGBTQ person to run for US congress. As an author and activist, his Data Unions redefined the labor movement and personal data as the neutral resource driving all corporate productivity. As an entrepeneur, he established the first international standard certification for corporate diversity and inclusion. His bio-political philosophy, Inclusionism is at the forefront of Human Rights advocacy and international relations. JFK has incubated the data industry via his founding of The Data Union and Personal Data Week conferences. As a serial entrepreneur he has founded multiple companies across the InsurTech, Fintech, and AdTech sectors.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Pacific Council.